I’ve been thinking about drugs, wars, Christmases, and your hospital (the one you work in and/or the one you go to as a patient).

January 7, 2015 | In: I've Been Thinking

On my daily walks, I’ve been listening to Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. I’m at Christmas of 1943—the year Bing Crosby’s newly recorded “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” began tugging at souls on radios across America. The tug persists.

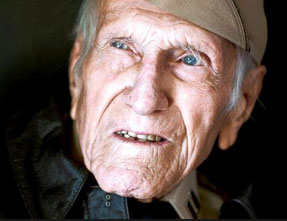

Though the bestseller’s central figure, Louis Zamperini, did not make it out of the POW camp and home for that Christmas, he did, by the grace of God (his words), make it home to Torrance, California, for the Christmas of 1945. I would arrive three years later for my first Yuletide in the neighboring town of Compton. Louis went on to spend no fewer than sixty-eight more holiday seasons with loved ones. Not incidentally, while he was a captive in Japan, the miracle drug penicillin was mass produced and issued by the Allied forces on the other side of the globe in 1944, ensuring that countless soldiers would be home for Christmas. This past July, Louis succumbed to pneumonia and died at the age of ninety-seven.

Though the bestseller’s central figure, Louis Zamperini, did not make it out of the POW camp and home for that Christmas, he did, by the grace of God (his words), make it home to Torrance, California, for the Christmas of 1945. I would arrive three years later for my first Yuletide in the neighboring town of Compton. Louis went on to spend no fewer than sixty-eight more holiday seasons with loved ones. Not incidentally, while he was a captive in Japan, the miracle drug penicillin was mass produced and issued by the Allied forces on the other side of the globe in 1944, ensuring that countless soldiers would be home for Christmas. This past July, Louis succumbed to pneumonia and died at the age of ninety-seven.

This past December 1, sixty-five-year young Loretta Macpherson of Bend, Oregon, was in the thick of her own war, supported by a skilled team of caregivers who performed surgeries and prescribed drugs with the reasonable expectation that she would be home with her loved ones for at least another Christmas, if not many more. She wasn’t and won’t be.

This past December 1, sixty-five-year young Loretta Macpherson of Bend, Oregon, was in the thick of her own war, supported by a skilled team of caregivers who performed surgeries and prescribed drugs with the reasonable expectation that she would be home with her loved ones for at least another Christmas, if not many more. She wasn’t and won’t be.

Below is the hospital’s public account of Loretta’s fateful visit to its emergency room—a visit prompted by anxiety and concerns about the medications she had been taking following brain surgery in Seattle around Thanksgiving:

- On Monday, December 1, 2014, Loretta Macpherson came to the St. Charles Bend Emergency Department for treatment following a brain surgery at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. The physician who cared for Ms. Macpherson here ordered fosphenytoin, an antiseizure medication, to be administered intravenously.

- The drug was correctly entered into the electronic medical-records system, and the correct order was received by the inpatient pharmacy.

- The order was read in the inpatient pharmacy, but an IV bag was inadvertently filled with rocuronium—a paralyzing agent often used in the operating room.

- The label that was printed from the electronic medical records system and was placed on the IV bag was for the drug that was ordered—fosphenytoin, although what was actually in the bag was rocuronium.

- The vials of rocuronium and the IV bag that was labeled “fosphenytoin” were reviewed without the error being noticed.

- The IV bag was scanned in the emergency department, but because the label on the bag was for the drug that had been ordered, the system did not know to sound an alarm.

- The bedside caregiving staff had no way of knowing the medication within the bag was not what had been ordered.

- The paralyzing agent caused Ms. Macpherson to stop breathing and to go into cardiopulmonary arrest. She experienced an anoxic brain injury. She was taken off of life support on Wednesday morning and died shortly thereafter.

“It would be terrifying to receive a paralytic if you were awake and alert,” blogged my hospital pharmacist friend Jerry Fahrni. “The drug paralyzes you, but your other senses remain intact.” Just visualizing this pushes me to the edge of panic, not unlike what I felt while reading Zamperini’s account of being confined for weeks to a box with the footprint of a coffin after being captured by the Japanese.

My thoughts and prayers go out to and up for Loretta’s family. I am also extending my enlistment in our war on preventable medication errors. Though none of us can number our days, I’m just over two-thirds of the way to Zamperini’s age when he died and to my father’s, who is still living. In any instance, however many years remain, I intend to continue recruiting hospitals to arm themselves with technologies and accompanying best practices that have proven to prevent the kind of errors that kept Loretta from being with her family this Christmas.

For nearly two decades with a number of you, I have campaigned for bar-code scanning of patients and medications at the point of care to ensure that the right strengths of the right drugs (whether penicillin, fosphenytoin, rocuronium, etc.) are being given to the right patients in the right doses at the right times. While we may be encouraged that around two-thirds of hospitals are now scanning most patients and medications at the point of administration, I do not plan on retiring from this branch of service until not a hospital serving our country would have it any other way. And I am happy to say that we are finding allies across the world in this good fight.

But let us never forget that the efficacy of scanning at the point of care hinges on the accuracy of labeling medications upstream. In 2004, we won the war we waged with the FDA, convincing the administration to require that manufacturers include bar codes on labels of all immediate drug packages. However, while most drugs packages make it from the manufacturer to the bedside without changes, many IV medications require compounding and additional labeling in hospital pharmacies—high-risk IV medications like the one errantly compounded and responsible for killing Loretta.

Without question, pharmacies should use bar-code scanning systems to verify ingredients when compounding IVs. As noted by the St. Charles administrators in points six and seven above, scanning at the point of care may verify that the right bag is given to the right patient, but it could not detect when a bag is filled with rocuronium instead of fosphenytoin as the physician had ordered.

As we move into a new year, only 5 or 6 percent of US hospitals are scanning to verify ingredients when preparing compounded sterile products. That was the adoption rate for scanning at the point of care a decade ago. Like I said, I won’t be retiring from this battle any time soon.

What could I do to recruit you for this war, if you are not already with us in the trenches? Your hospitals, the one you may work in and/or the one in which you will eventually be treated, are not exempt from human errors any more than the fine hospital in Bend.

The heading of the Institute of Safe Medication Practices’ December 18, 2014 “Medication Safety Alert” admonishes, “Tragic error with neuromuscular blocker should prompt risk assessment by all hospitals.” The alert begins, “There but for the grace of God go I. Those words are apropos for all hospitals in light of a recent, widely reported medication error at a hospital in Oregon.”

As patients, I hope you will provoke your hospitals to feel uncomfortable if they are not using bar-code verification systems at the points of preparing and administering medications. As hospital employees, I hope you will call your hospitals to arms, not only to protect their patients but also to protect their pharmacists and nurses from accidentally harming those under their care.

If your hospital needs motivation for enlisting in the bar-code war, please let me know how you think I might help.

Hospitals developing strategies for employing bar-code medication preparation systems will greatly benefit from procuring the latest Neuenschwander report In The Clean Room, A Review of Technology Assisted Sterile Compounding Systems in the US.

Let’s do what we can to ensure that those we treat and those we love are home for more Christmases.

What do you think?

Mark Neuenschwander aka Noosh

4 Responses to I’ve been thinking about drugs, wars, Christmases, and your hospital (the one you work in and/or the one you go to as a patient).

Ray Vrabel, PharmD

January 8th, 2015 at 5:42 pm

In my case, you know that you are preaching to the choir. I’m a firm believer in the use of barcode scanning, whether it is at the point-of-care (i.e., bedside), in the IV room (i.e., for IV compounding and preparation), in the outpatient pharmacy (i.e., for prescription preparation, or elsewhere where medications are dispensed (i.e., in the central pharmacy or with the automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) on the nursing units). Barcoding in all of these cases is done to make sure that the person performing the task has that right “stuff” (i.e., pills, vials, IV bags) for the particular task they are performing.

While barcode scanning in the IV room of this hospital might have prevented this error, the problems in this hospital appear to be deeper than that. This is not a small hospital; it is 260 beds and it is ranked as the Best Hospital in the Central Region of Oregon by US News & World Report. I’ve not be able to determine what electronic health system they are using and what, if any, medication automation they are using in the pharmacy or the rest of the hospital. I do know that they have a da Vinci Robot and if they can offer that for their patients, barcode scanning would be inexpensive in comparison. Then again, barcoding doesn’t generate any “new revenue”, but as you’ve noted, it does SAVE LIVES.

Why was a paralytic drug like rocuronium, which is primarily used in the operating room, easily available to the staff working in the IV room. The best method to prevent this specific error is a tried and true forcing function, not having the drug readily available. Unfortunately, this drug, like fosphenytoin needs to be refrigerated. Were they both stored in the same refrigerator? Preferably not! If they were stored in the same refrigerator, was the paralytic, rocuronium, segregated in any way to make someone “think twice” before they accidentally grabbed that drug instead of what they were looking for (fosphenytoin in this case). Best practices, like these, would have gone a long way in preventing this type of error from ever occurring even in the absence of barcode scanning.

In your report that you mentioned, I understand that you discuss some of the new technology solutions that are available to assist pharmacies with the accuracy of the IV preparation process. I call these IV Workflow (IVWF) automated solutions, since they attempt to address the entire IV preparation process. Most of these use barcode scanning, but some also use imaging and gravimetrics to ensure accuracy. All of these are great to have, but they will require an additional purchase and installation by the hospital.

There is another option for some hospitals who have already implemented bedside “bar code medication administration” (BCMA). Some of the EHRs that offer BCMA, also offer a barcode scanning solution that can be used both in the central pharmacy for dispensing and in the IV room for IV preparation. Since, these are an extension of an existing system, these can probably be implemented at much less cost and without maintaining another “system” in the hospital. I would be curious if this hospital has implemented BCMA and if their EHR vendor has a “bar code medication preparation” (BCMP, as you have coined) solution available. If so, why haven’t they implemented it?

Granted, these new technology IVWF solutions offer additional tools (e.g., imaging and gravimetrics) to assist the pharmacist with the checking process, but simple barcode scanning during the IV preparation process will prevent the types of “wrong drug”, “wrong solution” errors that are the most common, and the type that would have been caught in this example.

I’ve been practicing in hospitals for over 40 years and I can attest that there are a lot of opportunities for things to go wrong if standard procedures and processes are not carefully followed. Then, there is the human factor. We are not perfect and we make mistakes. Barcode scanning helps us catch those simple, human error mistakes that can be made (i.e., using the paralytic medication vial instead of the anti-seizure medication vial).

This causes me to ask the following question: Don’t patients have the right to know if the hospital where they are being treated is using barcode scanning anywhere that medication errors could be made: at the bedside, in the central pharmacy, in the IV room, at the automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs), and in the retail pharmacy (if the hospital has one)? Different organizations have “rating programs” to rate hospitals for various “quality” measures (e.g., Leapfrog, Healthgrades, HIMSS, US News & World Report, etc.). We need a Hospital Barcode Safety Scoring System. If a hospital was using barcode scanning in all of the areas previously mentioned, they would have a “Five Star Barcode Rating”.

We could publish a list of the “Top Barcode Scanning Hospitals” in the US, listing those hospitals that have a Five Star rating. Hospital marketing departments could list this information on their website like they do other quality factors. When do we start this journey? Let’s begin the delay…

mark neuenschwander

January 13th, 2015 at 11:02 am

I like singing in this choir with you, Ray. I FULLY agree with everything that you have written here.

I understand that the hospital did have a bar-code enabled workflow system in their clean room and then shifted to a different HIT vender, which for some reason could not interface to it.

“Top Barcode Scanning Hospitals.” I love it. Let’s talk more about this.

In the report, we did not cover EHRs that offer IVWF systems. We understand that while at least one does, it is not yet functional. Let’s talk more about this as well.

Also,

Ray Vrabel, PharmD

February 5th, 2015 at 1:11 pm

For the record, I wanted to document the fact that MEDITECH (Client Server Version, not Magic) has had the ability to perform barcode checking during sterile and non-sterile compounding procedures for over 8 years. This feature is available without additional cost, if the hospital has implemented BCMA. When you compare these features with other IV Workflow automation systems, they are unique in that they only perform the barcode medication preparation (BCMP) checking portion of the IV additive process. They do not have any image capture or gravimetric technology and rely on direct observation by the pharmacy to perform the final check of the IV admixture solution.

Likewise, Epic has had barcode checking of sterile and non-sterile compounding procedures since 2012. As with MEDITECH, there is no additional charge to use this functionality.

I have recently chatted with pharmacists using both of these systems and they appeared to be very satisfied. These BCMP-only capabilities have the opportunity to catch the most serious of the possible medication errors that can occur during the IV additive workflow process (i.e., wrong drug, wrong strength, wrong bag) and it is my opinion that BCMP should be the minimum requirement for the preparation of all IV admixture in all hospitals, regardless of size. Hopefully other EHR vendors will follow the lead taken by MEDITEC and Epic and include BCMP along with their BCMA solutions. In fact, I learned recently that one of the other leading EHR vendors will be offering the BCMP capability this year to their customers.

Hopefully, all of this will bring us closer to enhanced medication safety in the IV rooms of every hospital in the country…!!!

Mark Neuenschwander

February 6th, 2015 at 12:33 pm

Thanks Ray. Glad to be in the cause with you.