I’ve been thinking about lawnmowers, eye drops, smart phones, and glue.

November 8, 2011 | In: I've Been Thinking

If you grew up in church, you probably know about eating Sunday school paste. My kids liked the hint of wintergreen. Good thing it was harmless because a lot of kids dipped, and more than a few liked it. But hey, no harm, no foul.

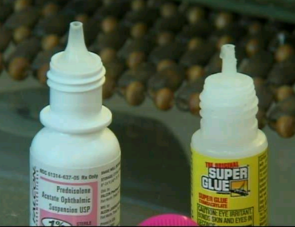

Not so for the Phoenix lady last October who ended up in an ER because she reached for eye drops and mistakenly picked up Super Glue. One responder suggested the lady was crazy for not observing the differences in size, shape, and color of the containers. What is crazy is that the error seems to occur periodically. Like this October, when a 69-year-old Maryland man said, it felt “just like I lost my eye” when he made the same mistake.

Not so for the Phoenix lady last October who ended up in an ER because she reached for eye drops and mistakenly picked up Super Glue. One responder suggested the lady was crazy for not observing the differences in size, shape, and color of the containers. What is crazy is that the error seems to occur periodically. Like this October, when a 69-year-old Maryland man said, it felt “just like I lost my eye” when he made the same mistake.

I know a very sane person who mistook contact lens cleaner for eye lubricant. At that time, the bottles were similar in appearance—to say nothing that both had to do with eye care. The episode was insanely painful and injured her eyes—temporarily, thank God. The industry has since changed the packaging.

Last month, an ISMP Medication Safety Alert brought yet another pair of sound-alike, look-alike (SALA) drug names to our attention: DUREZOL and DURASAL. In the long list of SALA’s, it’s hard to find two that could be more easily confused.

Granted the containers do not look alike. DUREZOL is in a white plastic squeeze bottle containing corticosteroid eye drops to reduce inflammation and pain following ocular surgery. DURASAL is in a brown glass bottle with a brush applicator for spreading the caustic liquid on warts for removal.

Granted the containers do not look alike. DUREZOL is in a white plastic squeeze bottle containing corticosteroid eye drops to reduce inflammation and pain following ocular surgery. DURASAL is in a brown glass bottle with a brush applicator for spreading the caustic liquid on warts for removal.

Though ineffective, my guess is it wouldn’t be that big a deal to apply eye drops to a wart. But applying wart-removal fluid to your eyes? Do eyes get warts?

The first DUREZOL/DURASAL mix-up reported involved a pharmacist misreading a doctor’s prescription for the eye drops and dispensing the wart remover instead. The patient brushed [1] the acid in his eyes, suffered “grievous personal injury,” and filed a $1 million lawsuit against the pharmacy.

When confronted with SALAs, ISMP says some drug companies simply “respond with a letter stating, ‘Reading the label is Nursing 101,’ implying that labeling, packaging, and nomenclature problems lie solely with the practitioner who did not read the label correctly.”

Similar sentiments were expressed during an ASHP LinkedIn Discussion of the DUREZOL/DURASAL debacle. After a number of reasonable fixes were suggested, one discussant added, “Still, nothing takes the place of good-old fashioned reading.”

Okay, that might be a helpful word for the practitioner, but what about the patient? Granted, “Wart Remover” is spelled out beneath the drug name in good-sized print. And the instructions are unambiguous: “Using the brush applicator supplied, apply twice to entire wart surface.” Shouldn’t patients read too? Of course—if they can.

It’s too easy to assume. Like the billboard I saw on a Florida highway a few years ago that read: “Have a literacy problem? Call 800-READ-NOW.” Yeah, right.

I’m thinking about the 14 percent of our U.S. adult population who can’t read. This year, the National Institute for Literacy estimated that 47 percent of adults in Detroit are “functionally illiterate.”

I’m grateful for ISMP’s persistence in collecting and reporting SALAs and for their unrelenting appeal that we all do our part to keep preventable errors from being repeated. So I’m wondering if there’s more we could do to communicate critical drug information to nonreading patients.

Here’s an idea: Briggs and Stratton is putting 2D bar codes that they call Power Codes (it’s a guy thing) on their motors, which when scanned with smart phones link lawnmower users to an array of important information like FAQs about operation and maintenance in English and Spanish. More reading you say. Not necessarily. Scanning QR or DataMatrix [2] codes on DUREZOL and DURASAL containers could link patients to videos pronouncing the name of the drug, stating what it is for, showing how to squeeze drops into an eye or brush fluid on a wart, and issuing warnings.

Here’s an idea: Briggs and Stratton is putting 2D bar codes that they call Power Codes (it’s a guy thing) on their motors, which when scanned with smart phones link lawnmower users to an array of important information like FAQs about operation and maintenance in English and Spanish. More reading you say. Not necessarily. Scanning QR or DataMatrix [2] codes on DUREZOL and DURASAL containers could link patients to videos pronouncing the name of the drug, stating what it is for, showing how to squeeze drops into an eye or brush fluid on a wart, and issuing warnings.

Of course, I’m assuming that people who can’t read will have smart phones. I realize some don’t. But many do and are fairly skilled with them. I’ve seen preschoolers use them to view pictures and play games. DataMatrix codes aren’t going away, and QR codes are showing up in more and more magazine ads as well as on products.

Vintners are using QR codes on bottles to link sophisticated connoisseurs to video clips, touting their wines’ vintage, aromas, and flavors and suggesting perfect pairings. If it’s good for lawnmowers and wine, why not drugs?

What do you think?

![]()

Mark Neuenschwander a.k.a. Noosh

BTW: I’m sad to report that my grandchildren’s Sunday schools do not offer edible paste. I hope the kids turn out all right.

Copyright 2011 The Neuenschwander Company

[1] Hmm. It’s not as easy as you might think to solve SALA issues. For example, the Maryland Super Glue man suggested, “Maybe the company should think about instead of putting a dropper, maybe a brush that you can apply glue.”

[2] For illustrative purposes, I’ve added DataMatrix codes to the DUREZOL and DURASAL containers in the picture.

3 Responses to I’ve been thinking about lawnmowers, eye drops, smart phones, and glue.

Dennis Tribble

November 9th, 2011 at 11:44 am

Mark,

All this underscores the futility of relying on human diligence in a world that is now over-populated with choices.There are a variety of extremely well-researched (not to mention old) publications from high-reliability industries (like nuclear power) that provide insight into the point at which human diligence fails. That number is surprisingly high (like between 3% and 10%) even for highly-trained professionals.

What this means is that strategies that ultimately rely on human diligence are also likely to fail. Tallman lettering cannot create the huge number of visually recognizeable names needed to clearly differentiate products; nor are there enough colors that can be readily identified when standing alone (as opposed to being compared to another color). These strategies are band-aids on a problem; they may reduce some of the pain, but they cannot, will not measureably move the needle on medication safety.

This is why BCMA (or BPOC, or BMV… take your choice) is so important. The bar code scanner, and the software behind it are incredibly literal, and have no mental processes that can cause them to see DUREZOL (or the number that represents it) when they were supposed to see DURASAL. The scanner, and the software behind it, are capable of diligence that is well beyond what we as humans can achieve.

Note that I said capable. What remains as a significant roadblock to achieving that capability is the incredble amount of work needed within each and every institution to maintain a current and complete library of the bar codes they encounter (or the NDC’s within those bar codes, if the software is smart enough to isolate and use it).

Indeed, at a webinar on RxNorm not long ago, Stuart Nelson effectively indicated that the FDA had abandoned all pretense of knowing what NDC’s are in the field or what they represent. They no longer even attempt to keep their public database current.

That is why I am urging everyone who chooses to comment on the FDA query about using 2-D bar codes to include commentary on the vital need for a FREE, reliable, and current database of NDC’s currently in the supply chain. I did…

Dennis Tribble

Barbara Olson

November 9th, 2011 at 9:15 pm

Thank you, Mark and Dennis. What’s wrong, why, and what you can do about it on one screen (in a font size middle-aged eyes can read). Plus a story or two for a smile.

Mark Neuenschwander

November 11th, 2011 at 2:39 pm

Amen brother. Thanks Dennis.